Blog

As a key player in the local construction industry, Camtech is committed to staying up-to-date on the latest national legal news and standards that impact our clients and our work.

The Flint Fiasco: What Went Wrong in Flint, Michigan, and Lessons for Mechanical Plumbers

Five years after the Flint water crisis in Michigan, the country has analyzed and identified factors which contributed to the escalation of the disaster. These factors serve as important reminders for the plumbing industry in New York State and nationwide, and have provoked the passage of New York laws that directly impact plumbing and mechanical companies.

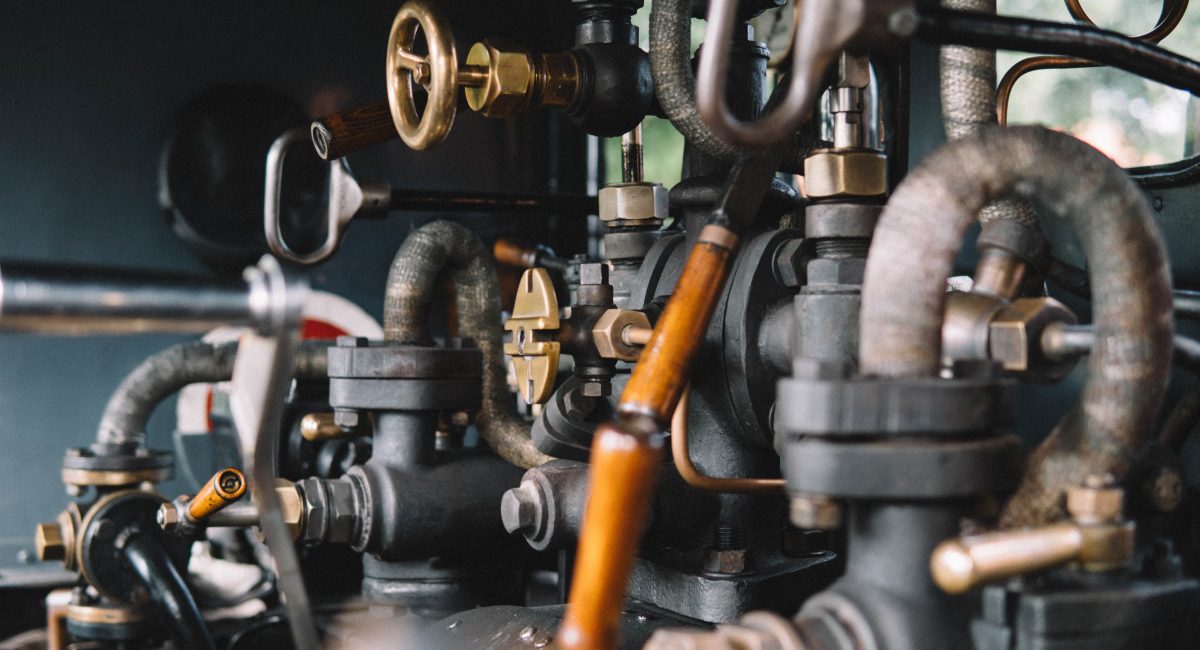

Factors which provoked the pervasive effects of the Flint water crisis include shortfalls of municipal decision making, and — more pertinently — a failure to identify aging plumbing infrastructure. The aged plumbing infrastructure was composed largely of lead; it was the most common material used to make the pipes that transported Flint’s water to water mains, and the most common material used to make Flint’s service lines. Further, the solder used in Flint to connect copper pipes and fittings contained high concentrations of lead, and many of the manufacturing faucets and plumbing components was made of a leaded alloy.

While lead piping and plumbing components were far more common prior to Congress’ regulation of such material in 1986, much of the pre-1986 infrastructure in Flint was not immediately replaced. Flint replaced some of the lead piping which it was legally obligated to replace, but the lead service lines that were not Flint’s direct responsibility and many lead service lines connecting households and other customers were never replaced.

The Environmental Protection Agency specifies the allowable standard for lead in water at 15 parts per billion, and this standard must be met in 90% of water samples taken in a given water supply. Testing of Flint’s water supply at the height of the catastrophe indicated the water had 104 parts per billion of lead — an amount wholly unsafe for human consumption.

In March 2017, a Detroit district court approved a lawsuit settlement granting nearly $100 million of state funding to tear out the lead-based and galvanized-steel water lines leading to 18,000 homes in Flint. The settlement, and extensive water infrastructure overhaul between 2016 and 2019 that replaced 7,000 municipal water transport lines and lead service lines had reduced the lead in Flint’s water to 4 parts per billion.

Some practice pointers that mechanical plumbers can take from the Flint crisis include an awareness that buildings constructed prior to the 1980s may have a lead piping infrastructure. Such knowledge is useful for the responsible monitoring of the condition and notice to keep an eye on states of corrosion. Further, while municipalities will replace some lead piping on its grounds, lead service lines are ultimately the legal responsibility of the individual property owner. In New York, sellers of residential properties are now legally required to disclose the existence of any lead plumbing, and its precise location.

-Published October 2019

For more information on the aftermath of the Flint, Michigan, water crisis, see Thomas Marcy’s September 2019 article: “Five years into the Flint Water Crisis, what are the lessons for managing our water infrastructure?”

For more information on the standards mandated for safe drinking water, see the Safe Drinking Water Act adopted by Condgress in 1974 and codified as 42 U.S.C.A §300f and 40 C.F.R. Part 141.

Carrington is a 2020 graduate of the University at Buffalo School of Law.